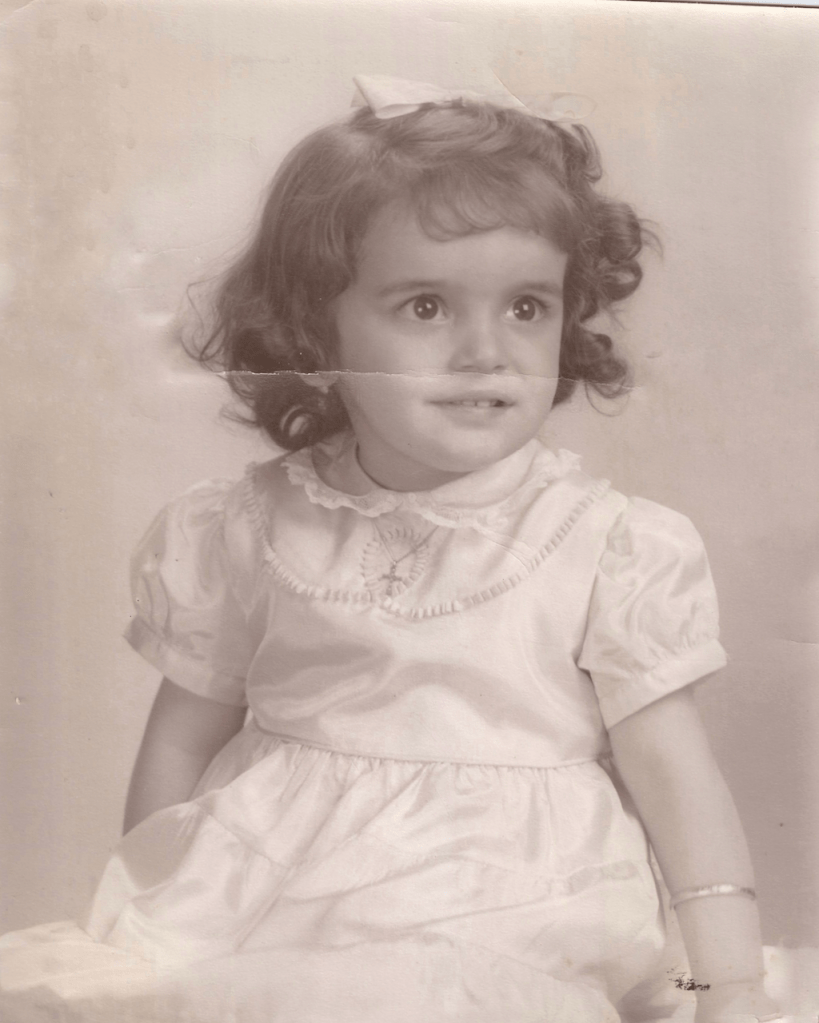

My pretty enough mother was always worried that we, her children, would have large noses. She would point to her own and my father’s as examples of noses that were simply too big. It seemed, however, that with sufficient and sturdy conviction, she and we could will these away. And, as fate and faith would have it, my sister, brother, and I are blessed with average, nearly admirable noses.

She also despised the color of her eyes, calling them yellow––“Cat’s eyes, they are.” I would stare at her as long as I comfortably could to get a good look but she would catch me and I’d have to quickly swing away my gaze. When I did sneak a look, I didn’t see the yellow at all. I saw brown which was the only color those nice people at Motor Vehicles would let her put on her driver’s license. To this day, I don’t know where she got this idea.

My mother was a devoted fan of blue eyes. She could list a whole series of notable and smart people she knew with blue eyes and for a while I thought that we would be blessed with these someday, as well. I thought this despite the fact that all my cousins, my aunts and uncles––all of them with very few exceptions––had dark brown eyes. I just suspected that if we prayed hard enough, the treasure of blue eyes would be ours.

Our parents sent us to an Irish Catholic grammar school even though we were descended from French-Canadian and Portuguese-Azorean stock. My sister and I have talked about this, about how strange we felt in this school. We were dark-skinned compared to our little Irish friends in this school which took its Irishness seriously. A child did not have to be Irish to attend this school. A devout Catholic family or a family that was headed in that direction was all that was required. My mother made it clear to the principal that she wouldn’t mind being Irish herself. This was decades before a child could be proud of her ethnicity and could demand accommodations for culture, language and customs. This was an era where we child considered the foods we ate at home and the festivals their parents dragged us to an embarrassment. At St. James, we sang Irish songs, spent a week celebrating St. Patrick’s Day, learned the jig, and brought home Irish culture–whatever that was. In the mid-1950s, it was as good as any other heritage and as disposable, for the most part. Our parents laid their Americaness like a thick blanket over their nationalities––intending to suffocate it for good. My father fought in World War II and taught us the lessons he learned from that conflict. American people were heroic. As Americans, it was in our nature to know and do the good and noble thing. We were blessed to be American and doubly blessed to be Catholic and American.

These were the chief lessons of our eight years at St. James. The blessed good fortune of all this was weighed heavily with the awesome responsibility of being a good Catholic  child. Even now, four decades later, the language of this formation–grace, blessings, contrition, penance–remains like scaffolding in my brain and in vocabularly, even though I have attempted to destroy and expunge it many times. A good Catholic child lived in two places––in the real world full of temptation and in the temple of the Holy Spirit. We children easily comprehended the architecture of faith, enormously difficult for men of God to explain. We learned all this complexity easily, the way French children breeze their way through verb tenses that elude college graduates.

child. Even now, four decades later, the language of this formation–grace, blessings, contrition, penance–remains like scaffolding in my brain and in vocabularly, even though I have attempted to destroy and expunge it many times. A good Catholic child lived in two places––in the real world full of temptation and in the temple of the Holy Spirit. We children easily comprehended the architecture of faith, enormously difficult for men of God to explain. We learned all this complexity easily, the way French children breeze their way through verb tenses that elude college graduates.

We learned this arcanum readily because it provided a clear way to understand the world. Children seek clarity and order. They struggle against it, of course, by asking questions to see if this adult-given explanation makes sense and is compatible with their own developing stories about the world. But, as they bang their wills against the rules, they learn the boundaries of their adventures and just how far adults will let them go. The 1950s in the Catholic Church were a stark testament to this fact. Without benefit of referred journals, supported research, conferences, government grants or other artifacts, our teachers––all nuns. Sisters of Mercy––created an intact, tightly woven, bullet proof method of teaching us things that we would remember forever.

Of course, the habits they wore made them both strange and fearsome, as well as comforting and familiar. Long black robes, rosary beads worn like large necklaces, black shoes and stockings. Their faces were completely framed by a starched wimple at their foreheads, which wrapped around their heads, set off with a stiff bib that stretched over their bodices, nearly reaching their waists. We learned to read a subtle body language. It wasn’t much beyond second grade when we knew what they were all about. But, their real power spun around their knowledge of what we children we all about. Our mothers  warned us against wrongdoing, as all mothers will and used as ammunition the fact that no matter where we were, what we were doing, they would know. We could get away with nothing. This served as a magnificent check on our behavior, especially for the girls. But, even more powerful that our mothers’ omnipresence was the specter of the nuns as representatives of God who was truly all being, all seeing, all there and everywhere. And the Sisters, as his lookouts and lieutenants, could not only see around corners and under desktops, but could detect a whisper when you didn’t even know you were talking. They could not only see, hear, and smell what you could be sensed––they could also peer into our beings, see our wretched little souls and examine the sins we might be entertaining in our lack of grace and prayer.

warned us against wrongdoing, as all mothers will and used as ammunition the fact that no matter where we were, what we were doing, they would know. We could get away with nothing. This served as a magnificent check on our behavior, especially for the girls. But, even more powerful that our mothers’ omnipresence was the specter of the nuns as representatives of God who was truly all being, all seeing, all there and everywhere. And the Sisters, as his lookouts and lieutenants, could not only see around corners and under desktops, but could detect a whisper when you didn’t even know you were talking. They could not only see, hear, and smell what you could be sensed––they could also peer into our beings, see our wretched little souls and examine the sins we might be entertaining in our lack of grace and prayer.

Although we were very young, only six or seven years old, we were sorely tested by the devil and his workers. We faced daily temptations like calling each other bad names, dishonoring our parents, failing to bow our heads and recite the requisite prayers, and having impure thoughts. But being good was only half of the challenge. Important as the commandments and Catechism was a duty to suffer for our faith.

On selected Friday afternoons, we watched films in the school basement. The older students set up rows of folding chairs and we sat with our classmates in our assigned seats. We were led quietly downstairs and were not to speak with each other or with members of other classes. We paid a small fee to see movies like Cheaper by the Dozen, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, Heidi, and the like. We also watched religious movies about the miracle at Fatima and the stories of saints. We were supposed to pick up lessons from these movies. It was a new media-savvy way to reach the young barbarians.

During missionary season when the parish was visited by a priest, brother or nun who had been converting the heathens in poor countries, we would watch black and white films of the missionaries at work. I clearly remember a movie about a Maryknoll brother and the work he was doing he was doing to bring Christ to the pagans in China. In this movie, an army of Chinese peasants surrounded a tall, strong, dark-haired Maryknoll in a black cassock. They carried sticks, waving them angrily above their heads. and marching  in a circle around the priest on a dusty barren hilltop. His head was bowed and his hands were tied behind him. The film was very grainy and the camera seemed to jump around. The narrator spoke deliberately about the priest and his devotion to God, how he had not betrayed his faith despite being tortured to renounce Jesus. The crowd led him up the hill where a wooden cross stood. I cannot remember if the film showed the priest on the cross but to the mind of a second grade, it seemed like this would be next step in the story. I remember that we were terrified and that some of us were crying.

in a circle around the priest on a dusty barren hilltop. His head was bowed and his hands were tied behind him. The film was very grainy and the camera seemed to jump around. The narrator spoke deliberately about the priest and his devotion to God, how he had not betrayed his faith despite being tortured to renounce Jesus. The crowd led him up the hill where a wooden cross stood. I cannot remember if the film showed the priest on the cross but to the mind of a second grade, it seemed like this would be next step in the story. I remember that we were terrified and that some of us were crying.

We walked back to our second grade classroom saddened and silent, filing quietly into our seats. When Sister Frances stood at her desk, she placed the small tin missionary box on a student’s desk. On these Fridays, we were told to bring in a donation for the missions. The children who had spent their money on candy and treats at lunch sunk in their seats, their souls stained with the sin of greed and filled with regret. They quickly passed the can over a shoulder without looking at it. Children, who had saved their money, shook the can, loudly clanged in their nickels and passed it back with a smug look of victory on their faces. We were warned against this sin, a demonstration of pride, but some of us could not help ourselves. The nun pretended not to notice all this and busied herself with an attendance chart or something on her desk. After the bank made its way around the room, we placed our hands on our desk in anticipation of the last lesson of the day and homework for the weekend. Instead, she spoke about the film and about the beautiful sacrifice that was only available to God’s chosen people. She told us about courage and the importance of living our lives as children in Christ. “Denying the Lord is the very worst sin you can commit, children. You have been blessed to be born in the Faith.” We had heard this many times and took it seriously.

Then she asked, “How many of you are willing to die for your faith?” Our hands shot up as fast as they could. The boys yelled out, “Me, Sister! Me, Sister”, competing with each other to be the first to be sacrificed. The girls were quieter, polite, stretching our arms, waving them to catch her attention. She had us. We were all going to be martyrs and saints!

No child hesitated and said, “Excuse me, Sister, I will have to ask my parents.” No child asked, “Can you tell me when I will die and if it will hurt a lot?”

We were ready to go, happy to, in fact. Today, I try to put myself in that teacher’s place and I think, “Oh, my God, they are ready to go wherever we will take them! Do they know what they are saying? Do I know what I am asking?” And, I think, “What kind of game is this nun playing? What a crazy insane thing to ask a child!”

I also consider other parts of this scene. I think about being in the first row, third seat down, a member of the top reading group, looking at the other students so eager to die for Christ, feeling very grown up. I was proud of making this courageous and correct decision on my own. This was my way to certain sainthood. There were other paths, of course, but this was offered in a manner that we could understand. It was compelling and seductive. Being slaughtered by a pagan because we refused to renounce the Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church seemed noble and good. I don’t remember a second of doubt. I filed away this promise to die for my faith expecting that the good Sister would inform the proper authorities when the time came for me to go, to be crucified, burned at the stake, buried alive or otherwise disposed of in the most gruesome manner.

Perhaps, children at that time were more susceptible to adult direction. Perhaps, adults were less careful about the terrors they willingly placed in the paths of children. Perhaps, both contributed to our growing up terrified, not of the man next door, or the predator down the street, or the gun toting madman at the fast food restaurant––but of large, mysterious things, like the heathen anti-Christs, communism, and polio.

And, of course, we were frightened by the atomic bomb. We did exercises in school, practicing in the event of an attack by the Russians. Sirens would go off and we would file into the fallout shelter at school. We asked the nuns where our parents would go when the bomb went off and they comforted us by reminding us that our parents could take care of themselves. I worried that my father who drove a service truck around the state would not be able to remember the location of each and every fallout shelter when the bomb fell. It seemed to me that he was always in danger.

At the distance of almost fifty years, I can see clearly how children are trapped by the fears of they adults they grow up with. Our own terrors create demons for them to avoid. Children can put off some of these fears to parental weirdness, but others resonate for a long time. When the whole culture creates and animates these bogeymen, children must take heed. They must take cover and run.

In addition to warning us away from big noses and wishing us blue eyes and lighter skin, my mother also guarded us against profligacy, against pride and gloating, against being too pretty, too smart, too anything, lest this draw the attention of God and engage his punishments. Sometimes, I wonder what terrors and frights I would have instilled in my own children had I given birth.

It seems that children survive childhood by creating play and joy to counter the admonitions and fears visited upon them by their parents and teachers. Sometimes they do this deliberately. They cannot figure out why adults are not happier than they are. So, they act silly. They giggle. They try to entertain and distract us. At least for a time, children face their parents without fear, with abiding trust, with the assumption that they are loved and lovable. Although we adults think we are amusing and comforting our children, it is, in fact, the exact reverse. The truth is that children assure us as their caretakers. Children enter a world that we have created and they begin to build it again, weighing all that we have taught them and tossing off what seems wrong headed and mean spirited. And so, a seven-year old can pledge her faith in afternoon, take her teaspoon of cod liver oil at night, bite her tongue when someone calls her a bad name, and still sneak a book to bed at night when she is supposed to be asleep. She can read this book of stories about St. Dom Bosco, who juggled for Jesus, and about Saint Theresa, the Little Flower, who would rather die than entertain impure thoughts. She can try to make sense of those tales of childhood heroics. And, she can struggle to be a model of virtue while scheming to avoid detection and punishment from vigilant adults.

And in these conflicts, children work things out. They soon understand that there is the world that adults would like them to fashion, where you as a child are kinder, more forgiving, more tender, and wiser than the adults guiding you. And, very quickly, children take their own counsel and assemble their own views of the world, their own stories that set them apart from the place their parents know the world to be.